One fruit of India’s economic progress that people don’t think about enough is the increased number of hours Indians end up spending in ironical stillness. In more and more of these back breaking bouts of traffics I have noticed bikes and cabs with a sticker stating proudly “Farmer’s son” accompanied with a fitting graphic. In a country where the backs of our vehicles are home to some of the most creative and honest expressions of the freedom of speech, these stickers carry a lot of weight. However, this pride at coming from a farming family seems out of place to me when juxtaposed with reality. Let me explain why. The statement of pride felt misplaced not because it was unwarranted or immoral, it is after all no mean feat, especially in a country like India, to nurture such value from the land as our farmers do. This pride was misplaced for me because here was a son who comes from a family of that creates value from one the most valuable resources in the world, land. I am no entrepreneur or business school graduate but consider this. You are entrepreneur with a product that uses high value inputs whose value doubles every 10 years, mostly because of the high amount of value addition you put into it. You have the famed CEO work ethic too, working round the clock (in fact your workplace is devoid of all clocks). And the icing on the cake? Your product is essential to human survival. And the cherry on the top? Your industry is the largest and most pervasive component of the country’s inflation and other growth metrics which drive business sentiments in the entire economy, meaning your industry is “too big to fail” and at the forefront of government subsidies and support, receiving bailouts from the government out in the daylight with no moral objections from any quarter. Well, the salaried middle class of the country might grumble away quietly of course but the grumbles are too quiet and the salaried middle class too small a population to have any real effect. A product with these features in software technology would a venture capitalist’s dream. Yet, our farmers see per capita incomes that are no match for even for the urban unorganized sector in many cases. Their sons driving cabs in the cities, which by no means is a job to be understated in its importance and dignity but which given the potential for wealth generation in agriculture morphs into a stark reminder of our failure to empower our farmers.

What if there was a way we could uplift our farmers by providing them with all the security and assurance that a government employee has in India while providing them the opportunity to earn the exponential returns an entrepreneur earns? An idea that turns every farmer in India into a government entrepreneur, a step above a government employee. All this while the government does not dig itself into a fiscal blackhole and on the contrary ends up making large profits.

I believe I have a solution that though not perfect might be able to achieve these objectives while alleviating many woes that plague India’s agriculture. I would like to detail out this solution and then also explain where applicable, how the plan addresses an existing woe of the agriculture sector.

The solution I propose is for the government to become the mandatory first buyer and second seller of agricultural produce in the country. Let’s break this idea down through three aspects: production, acquisition and distribution.

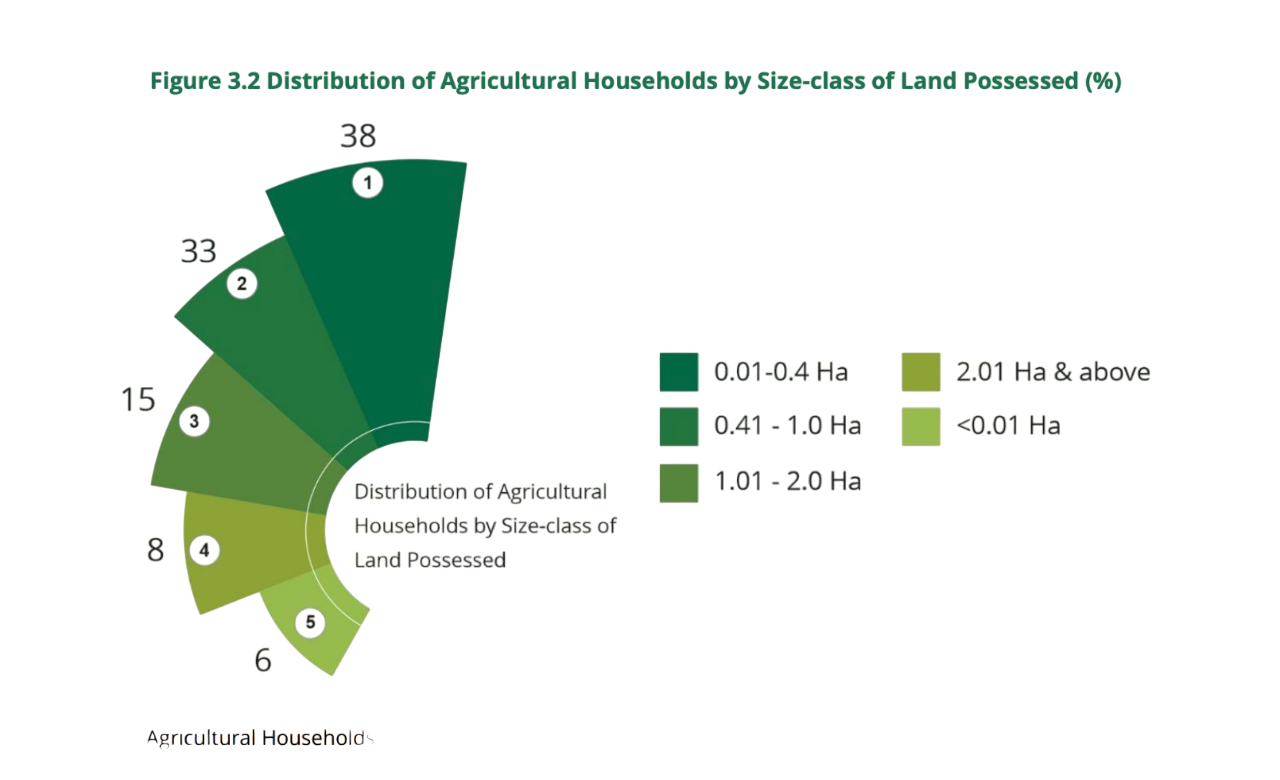

The first big focus of production must be productivity. Productivity in agriculture is best ensured by the ability of the farmers to use capital equipment and modern scientific methods of agriculture. Both these require a combination of large capital and debt-bearing capacity. Capital and debt in turn follow scalability and revenue certainty. So, how are Indian farmers doing on scale and capital investments? The shrinking size of average land holding in India tells a dire story of land fragmentation over generations that gnaws away at already unimpressive levels of productivity in Indian agriculture.

The above graphic sourced from the NABARD All India Rural Financial Inclusion Survey 2.0 (NAFIS) which was conducted in 2021-22 and published in 2024 paints a pretty clear picture. In fact, since the first NAFIS was published in 2016, the average landholding for farmers decreased from 1.08 hectares to 0.74 hectares, a fall of 31% over 5 years.

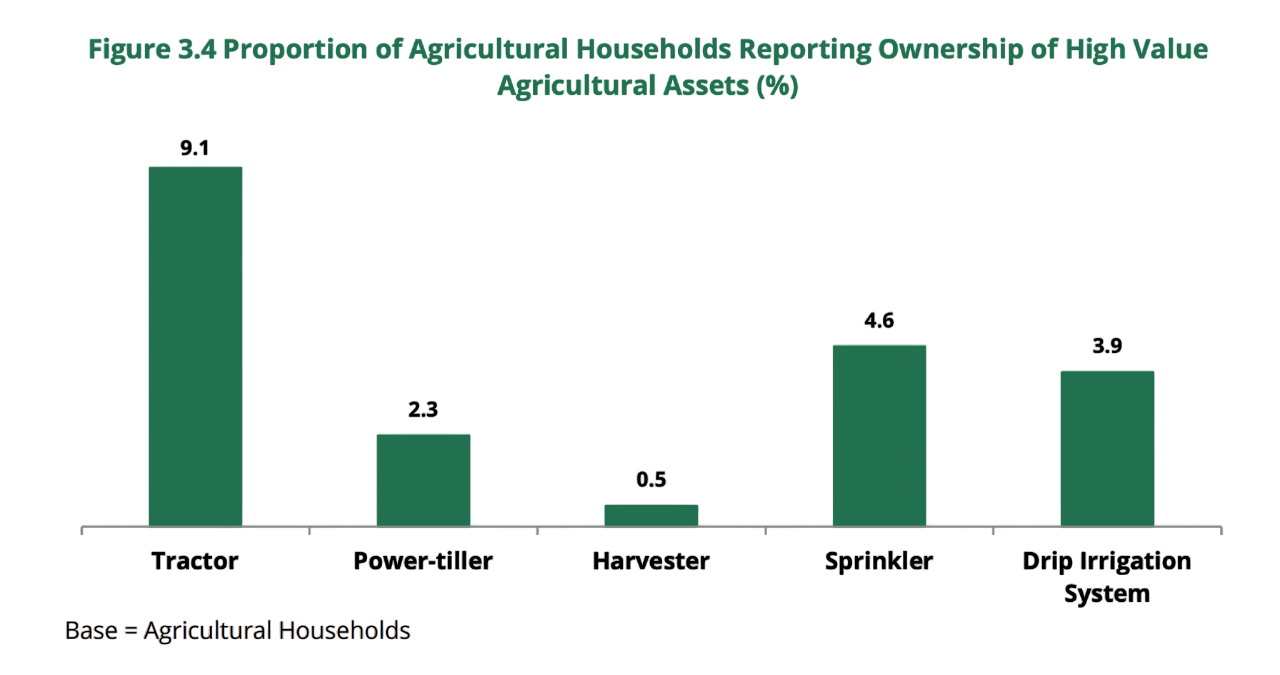

Couple this lack of scalability with the uncertainty of revenue from agriculture due to underdeveloped irrigation and cold storage facilities and you have the perfect conditions for minimized capital investment in agriculture as the graph below from the same survey clearly demonstrates.

The ownership of capital assets for agriculture does not breach the double-digit mark for any asset class. All these contribute to poor productivity in agriculture and incessant debt traps. The first step of my proposal is also the most difficult. The first step for this agricultural overhaul will require land redistribution across the nation on a scale never seen before in the nation’s history and probably in world history.

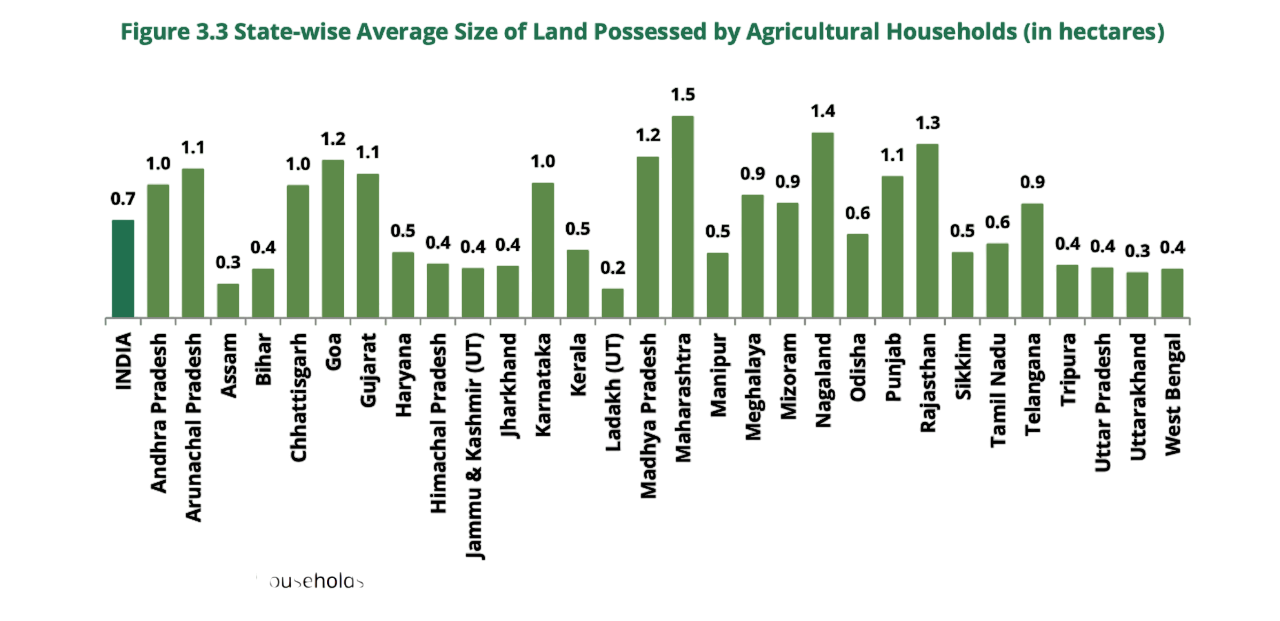

Now land holdings differ from state to state greatly due to geographical, economic and demographical reasons (see below).

What this land redistribution should result in is equal sized landholdings throughout a region. A nationwide standard size wouldn’t be feasible as the hilly states of the northeast and the north would have geographical constraints when it comes to large landholding sizes. Instead, the nation must be divided into broad agricultural regions which are contiguous akin to the railway regions in place and determine a standard landholding size for every particular region. These agricultural regions will come into play for other aspects of the plan as we move ahead. For example, the states of Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana can be one contiguous agricultural region with the mandated landholding size of 1 hectare. We will need to be flexible and adaptable when it comes to demarcating regions. For example, Kerala with a landholding size of 0.5 hectares on average and its geographical features could not feasibly be added to the region mentioned above, despite being a neighbour. It would instead be best suited to be a region of its own. With an average landholding size of 0.75 hectares. Setting the standard size above the current average landholding size would serve two crucial purposes. Firstly, it would allow the landholding size to be as large as feasibly possible. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly it will ensure that an overwhelming majority of farmers and tillers who don’t own any land will see an increase in their landholdings. The winners will exponentially outweigh the losers. Not something whose importance can be underestimated in building the political support for such a move.

Once the step one of land redistribution is completed, we must tackle the question of who grows what. Currently the monocropping obsession with wheat and rice, and heavy use of fertilizers and pesticides is rendering our lands barren and our water tables poisonous. It has also paradoxically resulted in nutrition deficiency in the population amidst bumper agricultural production in most years. Wheat and rice after all are important components of a healthy diet but not the only ones. Our current agricultural system has also resulted in many local and climate resilient crop varieties dying out leading our food security into peril.

A commission or Aayog will have to be set up to decide what needs to be grown and where it needs to be grown. The members of this commission must be the professors and scientists from all the 63 public agricultural universities in India and from eminent research centres in the country like ICRISAT and ICARs. Private universities and research groups must also be given a seat at the table. These members must be made ex officio. For example, the vice chancellors of the universities and the heads of the research organizations must become ex officio members of the commission, i.e., they become members of the commission as soon as they assume the position of vice-chancellor or head of institute. This mechanism would minimize the political motivations behind appointments to such a power body and ensure that the best scientific inputs are being received by the government. Let’s call this group of members of the commission, the expert committee. The other set of members of the commission must be the agriculture ministers of every state and union territory of the country along with the union minister for agriculture. This group can be called the ministerial committee which would ratify all decisions of the commissions with each minister getting one vote. This will ensure that the values of federalism are upheld and that states have a larger say in their own agricultural decisions. The third group of members can be prominent members of the industry and members of the civil society that must form the consulting committee and must be mandated with providing its inputs when sought.

Keeping in mind the obsession with acronyms of the current regime, this commission can be called KRIshi Yojana Aayog or KRIYA. Once formed, KRIYA must conduct multiple studies to determine certain key facts. Firstly, it must create the list of crops that can be feasibly and commercially grown in the country. Next it must conduct the average yield per hectare when growing these crops. Thirdly, it must determine what is the total average cost of all inputs used in the production of the crop. Lastly, it must determine the consumption and export of the crop in the country over the last few years and come up with a formula for determine a reasonably accurate level of production requirement for the crop. Let’s put these components in number. KRIYA determines that for Barley, the average yield per hectare when rainfed is 2 tonnes and when irrigated is 5 tonnes (this by the way are true numbers for the crop currently in India). KRIYA will then ascertain that the total cost of production (C2 is the most comprehensive and ideal cost metric that can be used) of Barley is ₹12,390 per tonne. We then ascertain that India consumes close to 2 million tonnes of Barley every year with its domestic production being around 1.75 million tonnes. KRIYA must then decide how much of this requirement of 2 million tonnes it intends to meet domestically. Let’s say KRIYA decides that it aims to produce 1.75 million tonnes in India. With an average yield of 5 tonnes per hectare, India would need to have 0.35 million hectares of land under Barley cultivation. If the agricultural region it wishes to distribute the production of this crop over has the standard landholding size as 1 hectare, then around 1,23,000 landholdings must grow Barley. KRIYA will then decide how many of these holdings go to which state in the agriculture region. Continuing with putting numbers to our examples, let’s say Rajasthan is allotted 75,000 of these landholdings. The method by which Rajasthan’s government chooses to allocate these landholdings withing its territory should be left to the state government to decide.

In practice, KRIYA will not allocate every crop individually. Instead, KRIYA will allocate crop bundles that would cover six agricultural seasons, i.e., 3 years as India has two agricultural seasons (Kharif and Rabi). This cycle of six season will predominantly be dedicated to Barley as the bundle is a Barley bundle however, it would also be interspersed with other crops in order to ensure crop rotation and soil rejuvenation. For example, the four seasons of Barley can be interspersed with one season each of legumes and potatoes. A landholding allotted the Barley bundle will have to grow these crops in this order over the next 3 years.

Now, addressing some concerns that might have cropped up (pun intended) with the production piece of the plan. Firstly, this reeks of Stalinist type state planning of a sector of the economy at first glance. Might even look eerily close to collectivisation or Mao’s great leap forward. This is none of those. Yes, there are socialist overtones to the land redistribution, but the redistribution serves a practical capitalist purpose – productivity. The market is not being edged out of agriculture either. The C2 measure of cost of production is directly linked to the market price of the inputs used and is determined for each year separately. The production targets used are also linked to the consumption data of the past few years. Consumption is inherently out of government control and is an intrinsic market force. What grows where is taken out of the hand of market forces, but this is in order to ensure that the crops are grown in areas that are environmentally best suited for their cultivation. The crop bundles will also specify the seed variety of a crop to be grown as part of it. This will ensure that local varieties of seeds are preserved which require far lesser pesticides and fertilizers. Now, even if you were to be convinced by the plan so far, the next question you might ask is how would you ensure that a farmer grows the crops you want them to grow in the sequence that you want them to. Changing agricultural behaviours is not an easy task as the failure of efforts to prevent stubble burning has proved. The answer once again lies with the market incentivizing the desired behaviour. The procurement phase of the plan will answer these concerns.

A slight digression before I delve into the procurement piece is that, apart from the list of crops that KRIYA determines can be feasibly grown domestically, KRIYA will also come up with a list of “Scheduled Crops”. These would be high value/ capital intensive crops that are not easy to grow or are in very scarce supply in India. Strawberries, mushrooms, oilseeds, etc. can be part of this Schedule. Scheduled crops would be out of the bundle system. Any farmer can rather than choosing to get allocated a bundle can make a 3-year commitment to instead grow a scheduled crop. These farmers may be from any agricultural region and any size in numbers.

Now with the procurement piece. The government would be the mandatory first buyer of all agricultural produce. The MSP will be transformed from Minimum Support Price to Mandated Selling Price. This would be the price at which the government will procure produce from farmers directly. The market price will be 2* C2. Every landholding will have a unique ID and the government will guarantee that it will buy any quantity of produce from every landholding. Here is where the concern of ensuring that the farmers grow the right crop in the right sequence and at the right place gets addressed. Recalling the Barley example, let’s say, for a landholding Zeta Farms, the crop bundle for the six seasons requires production in the sequence Barley >Barley>Legumes>Barley>Barley>Potatoes, the government will only buy Barley from Zeta Farms for the first season and only buy Legumes in the third. With the government being the mandatory first buyer (meaning their being no alternative buyers} the farmer will have to grow the crops as mandated. If Zeta farms were instead to produce oilseeds, the government will buy any quantity of oilseeds from them throughout the six seasons as oilseeds are a Scheduled Crop.

Now, let’s look at some issues this phase of the plan addresses. Firstly, it eliminates the middlemen that have exploited the farmers for so long. The farmers get a high price for their produce and revenue certainty. This assurance will help them acquire debts from formal institutions rather than informal ones and also help them secure better loan terms. This certainty will also encourage higher capital investment and innovation as the government guarantees to buy the entire produce of a landholding irrespective of the quantity.

The procurement phase also addresses the environmental and fiscal concerns. As the government is already guaranteeing to purchase the produce of the farmers at twice the cost of production, the government must end all subsidies on fertilizers and pesticides and no longer provide free water and electricity. Instead, these must be made part of the average C2 calculation. As the C2 of a crop is fixed and pre-determined for every year, the farmer consequently also already knows the price at which her produce will be bought. The fixed C2 that includes fertilizers, pesticides, water, and electricity will hence incentivize farmers to innovate and invest in order to produce the crop at a cost as below C2 as possible to maximize their profit margins. This would result in a great decrease in the use of fertilizers, pesticides and water in agriculture and lead to ecological replenishment. India allocated a whopping ₹1.7 lakh crore on fertilizer subsidies alone in the 2025 -26 Union budget. Imagine freeing up ₹1.7 lakh crores to be spent more productively elsewhere while not hampering the livelihood of the farmers. The concern that this procurement plan may end up sprawling a black market of its own by farmers choosing to produce high priced crops throughout all agriculture seasons is addressed by the fact that no black marketeer would realistically be able to compete with the prices that the government is offering. Prices that are deliberately set high to help create political support and to incentivise best practices and innovation. While the guaranteed procurement provides the farmers with the security and assurance of a government employee, the possibility of them innovating and investing to produce crop at lower costs to maximize their profits provides them with entrepreneurial opportunities for exponential returns.

Before I move to the final phase of distribution, which is more consumer facing, I would like to round of the provisions for the farmers.

The assured return on their land can also help bring all farmers under larger crop insurance schemes. Down the line, increased disposable incomes for the farmers will reduce the underemployment in the agriculture and will also stem the rural-urban migration that has often put a strain on the urban infrastructure. In order to ensure that the gains made from the revolutionary once in a lifetime campaign of land redistribution are not squandered away, landholdings must be perpetually frozen. People should not be allowed to sell or buy land nor be able to inherit or bequeath agricultural land. What people can be allowed to sell or bequeath must be the share in the revenue from the land. This will ensure that the landholdings do not get fragmented over generations while the wealth generation from the land can still be passed down generations, akin to stock in a company. This will also ensure that agricultural land by itself doesn’t lead to concentration of wealth and the value of the land is derived from the produce that the land produces. Ensuring constant initiative, innovation and investment rather than stagnation that may seep in in large rentier societies with large landholdings.

This scheme can also ensure during land redistribution that if it becomes infeasible to distribute land along all tillers that the tillers with no land holdings are formed into a cooperative and jointly own multiple standard-sized landholdings. This will help bridge the gaps of wealth inequality.

Now, finally coming to the distribution phase, this is where the government is, as a consequence of being the mandatory first buyer of agricultural produce, the mandatory second seller of agricultural produce. Here, the government must strive to build better cold storage facilities and distribution networks. It must also strive to shorten the supply chain to ensure that the consumers get a fair price and that the market is prevented from shocks. Here, I believe the government must restructure the food corporation of India and reduce its ownership to 51%. For the remaining 49% it must invite firms like Amazon, Flipkart, Zomato, Swiggy, Blue Dart, VRL, BigBasket etc. to take a stake in the firm. These firms must not be asked to pay money for these shares but instead be required to provide infrastructure and services to run the distribution network of agricultural produce in India. And yes, I include Zomato and swingy and BigBasket in this list in order to ensure that the distribution network covers doorstep delivery to the end customer.

This new FCI will procure the food from the farmers and then sell it at a 100% markup. That is, at a price of 3*C2. The FCI will also set a minimum and maximum order quantity for all agricultural produce to ensure that the orders aren’t big enough to result ion stockpiling and that they are not too small to be economically serviced. The FCI must partner with the Railways, airlines, shipping firms and by-road logistics firms to ensure that the orders are serviced seamlessly and timely. The expertise the private firms will bring in the user interface and customer experience will be invaluable in ensuring a stable and efficient supply chain. All participating firms must also be entitled to a service charge that the FCI will payout to them for every order fulfilled. With a 100% markup on the produce, the FCI will not become another case of a subsidized white elephant of a PSU that runs into losses. It will also provide it with enough cash outlay to build infrastructure and strengthen its supply chain. The participating firms will ensure that the FCI doesn’t have to build everything from scratch by sharing the use of their existing personnel and facilities.

The 100% mark-up might seem like a pinch at the pockets of the consumers, but it will in fact bring food prices down a great deal because in a system where food prices to the final consumer tend to 8 to 10 and even 15 to 20 times the price paid to the farmer, a 100% markup would result in a considerable drop in prices. The FCI will also ensure a stable price by building better storage facilities and distribution infrastructure. The supply chain till the final consumer can be as short as Farmer > FCI > Consumer as anyone would be allowed to buy from the FCI from anywhere from the country provided their order at least the minimum order quantity.

The FCI will also determine the proportion of the produce of a crop that is available for the exporters to buy for export to the rest of the world. This will help provide the government with a lever of control over export quantities during food shortages.

These realistic food prices would ensure reasonable food inflation which has over the years increased its share in the overall inflation in the economy. The inflation in the economy largely determines the interest rate policy of the RBI which in turn informs the investors’ mood about the economy as a whole. Stabilising this large part of inflation will help RBI and the government build better economic policies and help attract investors to the other sectors of the economy.

This system would require a complete overhaul of the agricultural economy and will require a major shift in the political thinking of the country. But once implemented, I believe it will help lift millions out of poverty. Completely change the rural landscape and result in a skyrocketing agricultural productivity. Productivity which will then bring down our need for more arable land and hence reduce the lost of forest cover too. This is not a magical solution of course and will require many nuances to be worked out and will require a lot of flexibility from a state that is used to rigid bureaucratic diktats. But if we pull this off, we will be able to finally usher our farmers and our villages at large out of the colonial cycles of poverty and oppression that we have renegaded them to. And maybe, one day, while I while my time away in traffic, it won’t be a yellow plated cab or a Swiggy rider with the sticker stating “Farmer’s son” but rather it would be a bulky and oversized Mercedez or BMW.

Leave a Reply